In other words, if our non-believing friends invite us for a dinner, party, fund-raiser, or whatever, unless there’s a really good reason not to, we should go. Often I hear Christians lamenting that they have no non-believing friends. Or that they don’t get to talk to their friends about weighty matters. Maybe a simple solution is to make it foundational to our lifestyle to go to their meals or parties whenever we’re invited.

Second, we need to make hospitality foundational to our own lifestyle. I would push this even further to suggest that we need to find creative ways to do hospitality. That’s because for many of us, the traditional forms of hospitality are impossible. Maybe we’re still living at home with our parents. Or we live in the back of a car! Who knows? But that’s where we can find workarounds. For example, we can order their coffee for them and then pay for it—our treat! Or we can turn up to someone’s place with a pizza. Or we can bake a cake and share it. In all of these examples, we still end up creating a space where we eat and drink together. And ultimately end up connecting, relating, and talking.

Third, hospitality is a form of generosity. Hospitality is costly. It costs time, effort, and money. But as a result, hospitality gives us social capital. This allows us to talk about matters—matters that our friends might not agree with—but they will give us permission to disagree because we’ve earned their trust. And if we’ve been generous to them, then they will most likely be equally generous to us by at least listening to our views, even if they don’t agree with what we’re saying. Hospitality also makes the host vulnerable—we’re opening up our private home to our guests. But in doing so, hospitality invites the guests to be vulnerable in return. This is a safe space where they can talk about private matters that are weighty to their heart.

But if all of the above is true, why do we still hear that there are two things that we must not talk about at a dinner party—viz., politics and religion? In other words, there seems to be a mantra that we should not talk about weighty matters over a meal. Instead, so we hear, we should only talk about safe subjects such as the weather and what TV shows we’ve watched lately. I think that this is because people often don’t know how to disagree well. So, how can we talk about weighty matters and disagree well at the same time? The next few points might help.

3. Learn the art of conversation

Do you ever find yourself talking about the weather and wondering why? Why are we so obsessed with asking each other about our weekend? Or why does the other person always ask about what my plans are for the vacation? Or why do they tell me to say hi to my wife and kids, when they could just pick up the phone and do it themselves?

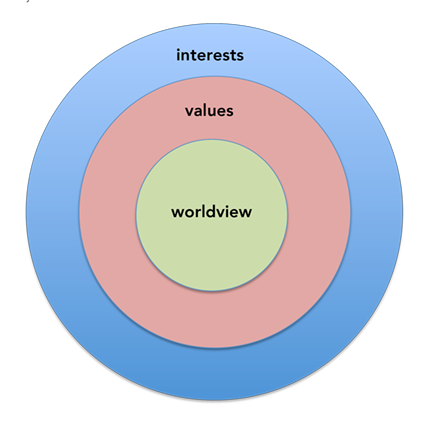

To understand this, we need to grasp that there are layers to a conversation, similar to the layers of an onion:3

Usually conversations begin in the outer layer of interests. What did you do on the weekend? What are you watching on Netflix? What are your plans for the vacation? What subjects are you taking? What do you hope to do for work? Who’s your NFL team? What movies do you enjoy watching? Where’s home for you?

That’s because, in this layer, the statements will be descriptive. They merely describe factual statements that are, by and large, seemingly easy to verify. For example, if I ask you what are your plans for the holidays, and you tell me that you plan to go fishing in Michigan, I’m not going to say, “I disagree!” If I ask you what you’re watching on TV, and you tell me that it’s Game of Thrones, I’m not going to say, “No, I don’t believe you—you’re lying!” And if I ask you what movies you enjoy watching, and you tell me that you enjoy James Bond movies, I’m not going to say, “No you don’t!” Or if I ask you what is your NFL team, and you tell me it’s the Chicago Bears, I’m not going to say, “I think you’re wrong about that.” As a result, this is a safe layer for conversations. The talk will be civil. There will be little chance of disagreement.

But in the middle layer, we enter the world of value statements. We make statements about preferences, ethics, value, and beauty. For example, in this layer, our friend might say, “Fishing is a cruel thing to do to the fish.” Or they might say, “There’s too much misogyny in Game of Thrones.” Or they might say, “James Bond movies are better than rom-coms.” Or they might say, “The football in the NCAA is superior to that in the NFL.”

In this layer, the statements are prescriptive. They have a sense of oughtness. They describe evaluative claims that are, by and large, difficult to verify immediately. As a result, there will be a high chance of disagreement. You might want to take the opposite side of the argument—fishing is not cruel, Game of Thrones is about female empowerment, rom-coms are better than James Bond, and the NFL is better than the NCAA!

This is why we find it difficult to have conversations about weighty matters. It is not because we lack courage, and not because we lack opportunities, but, because, in general, these conversations will end badly. There will be conflicting views. And there are friendships at stake!

But if that’s challenging enough, wait until we hit the central layer of conversations, where we start talking about worldviews. Here we make statements about what we believe to be reality itself. Is there a God? Is there life after death? Are humans good or evil? Are we individuals or a collective? Is there free will? What is the meaning of life? Is this all that there is?

For example, in this layer, our friend might say, “Fishing is cruel because there is no difference between a fish and a human being.” Or they might say, “Game of Thrones shows that the arc of history ultimately bends towards freedom.” Or they might say, “James Bond movies only make sense if you believe in good versus evil, but I think there is no such thing.” Or they might say, “The NCAA is superior because the players play as a team, but the NFL is too much about individualism.”

Our worldviews are the engine room that generate and drive our values. They are the interpretive lenses for how we understand the world of facts. As a result, if we have different worldviews, we don’t just disagree, we actually disconnect. We are sitting on two different mountain-tops with two different ways of understanding reality, two different ways of interpreting the evidence. For example, if our friend doesn’t believe in life after death, then it might make perfect sense to maximize the amount of happiness in this lifetime. Or if they believe that humans are just another species of life on this earth, it makes sense not to privilege our species over that of another.